The Congress of Vienna (1814-1815) was a series of diplomatic meetings that were held at the end of the Napoleonic Era . At the time, European countries found themselves ravaged by many years of war and rule by relatives and friends of Napoleon. These states successfully reasserted their independence and had to organize the continent in a way that ensured lasting peace within it. With this in mind, they gathered in the capital of Austria, inspired by certain principles and with the authority to reshape Europe. Their deliberations led to numerous changes in the map of the continent and set the stage for a period of great power politics known as the Concert of Europe. Because of that, the Congress of Vienna was a key event in the history of the nineteenth century.

Participants of the Congress and Their National Interests

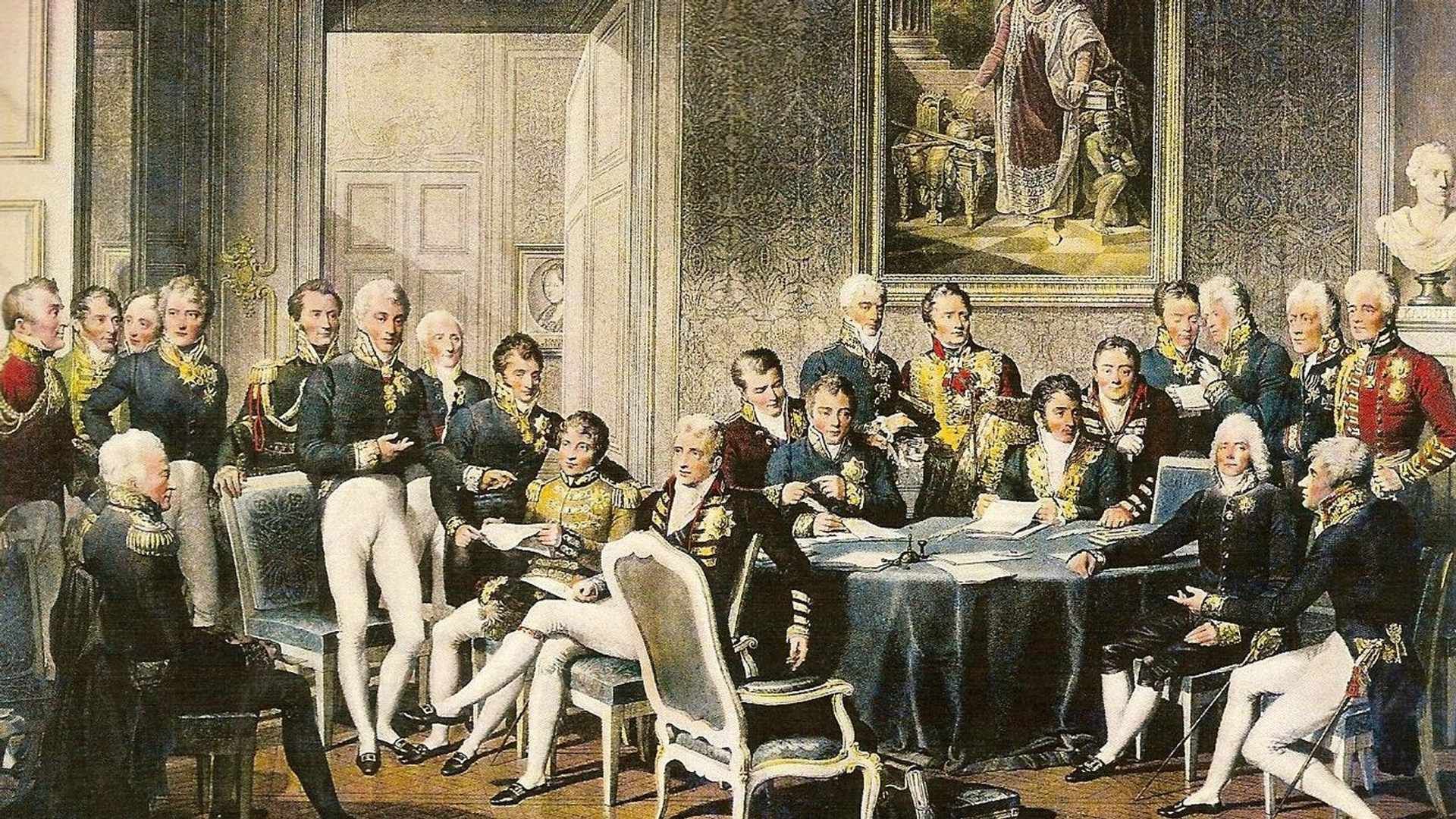

The Congress of Vienna was attended by many diplomats, foreign ministers and heads of state of European countries. Yet there were five countries that monopolized the discussions and that engineered the final settlement. These were the protagonists of the meeting and the national interests they espoused:

- Foreign Minister Prince von Metternich (Austria): According to Henry Kissinger, he was the main architect of the Vienna order. His “consummate skill was in inducing the key countries to submit their disagreements to a sense of shared values”. In doing so, he sought to maintain Austria’s political hegemony and a balance of power in Central Europe.

- Foreign Secretary Viscount Castlereagh (United Kingdom): He aimed at preventing France from regaining its status as a superpower and containing Russia’s aspirations. Britain wanted the continental countries to remain at peace and in equilibrium with one another, preferably respecting the wishes of smaller states. Meanwhile, it wanted to ensure British hegemony over overseas colonies, industries, and maritime trade routes.

- Tsar Alexander I (Russia): He was a conservative monarch who championed absolutism and wanted to combat any threat of revolution or republicanism. During the Napoleonic Wars, he had briefly considered refashioning Europe in liberal and constitutional terms, but he soon resumed his authoritarian tendencies. In Vienna, he wished to take control of Poland, expand Russian territory, and establish Russia as a major land power.

- Chancellor and Prince Karl August von Hardenberg (Prussia): Knowing about the historical rivalry between Austrians and Prussians, he wanted to secure the latter’s position in the lands of the former Holy Roman Empire. In particular, he wanted to annex all of Saxony and parts of the Ruhr.

- Foreign Minister Talleyrand (France): He had been Napoleon’s right-hand man in international affairs, but he remained in office following the rise to power of King Louis XVIII. His goal was to prevent France from being demoted to second-rank power and from being dismembered by the occupying powers. However, the King distrusted him and also conducted negotiations with the other states, separately.

Principles of the Congress

During the Congress of Vienna, certain principles guided the deliberations of European countries and were accepted by them as a framework for rebuilding the continent after the wars. These were the main principles of Vienna:

- Legitimacy: The French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars had dethroned several absolutist dynasties and had replaced them with other monarchs. Following the defeat of the revolutionaries, Talleyrand wanted to make sure that Louis XVIII kept the French throne, so he proposed the principle of legitimacy. According to it, all dynasties that ruled Europe before the Revolution were legitimate and had to be restored to power.

- Compensations: During the revolutionary period, France had taken control of many territories. Because this was unfair, occupied lands were to be redistributed among Europe’s powers, compensating them for war losses.

- Equilibrium: The map of Europe would not return to how it had been before the Revolution. Rather, a new map would emerge, because redistributed territories would be assigned with the aim to equalize power differences among the major countries. If every European power were satisfied with this settlement, there would be no reason for another conflict to break out.

- Interventions: Because absolutist regimes of pre-revolutionary Europe were legitimate, any attempt to oust them had to be tackled. Austria, Prussia and Russia formed the Holy Alliance, to intervene in other countries to suppress new revolutions, while the United Kingdom preferred to remain out of it. In any case, some authors claim that this alliance was nothing more than pious hope and that its interventions were self-interested rather than altruist.

Main Decisions of the Congress

In Vienna, the five major powers of Europe agreed upon a series of measures intended to craft a new international order in the continent.

Thanks to the work of Talleyrand, France was spared the humiliation of being entirely defeated. For example, the country’s territory would be a bit bigger than it was before the Revolution. Also, the French would have to pay an adequate amount of war reparations, and while they did not complete the payments, the country would be temporarily occupied by the troops of the victors.

Most of the decisions in Vienna revolved around the shuffling of territories, favoring countries that had opposed the French during the Napoleonic Wars, to the detriment of France and its allies. These were the main territorial changes:

- During the last phase of the French Revolution, Switzerland had been overrun by the revolutionaries and had been turned into the Helvetic Republic — a vassal state. Napoleon eventually had to reestablish the Swiss Confederation, but the country remained dependent on the French. In Vienna, Switzerland would be restored as a fully independent and neutral country, and Europe’s powers would guarantee its neutrality.

- Napoleon had created the Duchy of Warsaw in the region of current-day Poland. This entity was abolished and its territory was split between Austria, Prussia and Russia.

- Napoleon had created the Confederation of the Rhine in the region of current-day Germany. This entity was replaced by the German Confederation — an association of 39 German countries, politically led by Austria and economically led by Prussia. The goal was to prevent France from becoming a hegemonic power in Central Europe.

- Prussia would acquire the Rhineland and the Saxony, two regions that had great economic potential.

- Russia would acquire the Bessarabia (current-day Moldova and Ukraine) and Grand Duchy of Finland, because it had fought over it against Sweden.

- In order to compensate Sweden for losing Finland, the Swedes would acquire Norway — a region that had belonged to Denmark, a French ally. The Norwegians rejected this settlement, got into a war, but were ultimately defeated and forced to accept the rule of the King of Sweden. According to historian Eric Hobsbawm, this arrangement favored the United Kingdom, because two states would share control over the Baltic Sea. However, the unpopularity of the arrangement persisted and it would not last long.

- The United Kingdom took possession of certain colonies from the Netherlands, because the Dutch had been French allies — especially, Cape Colony (South Africa), Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and a part of the Guyana.

- In order to compensate the Dutch for losing these colonies, they would acquire Belgium, which was then the Austrian Netherlands, because Austria had been a French ally. This exchange of this territory would lead to the creation of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, comprising current-day Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg (the Benelux countries).

- In order to compensate the Austrians for losing Belgium, they would acquire certain territories in the Italian Peninsula. The Pope would regain control over territories in the same region, too.

In addition to these territorial adjustments, the Vienna powers also agreed upon other measures that changed world order at the time:

- The Society of Jesus would be restored, both in Europe and in colonial territories. It was a religious order within the Catholic Church that had been suppressed during the previous decades.

- Slave trade was condemned. Yet its actual abolition would only come many years later, following fierce resistance from countries that depended upon slavery, like Brazil.

Conclusion: European Order after Vienna

The Congress of Vienna began when Napoleon was seemingly defeated and sent into exile in Elba Island. While the powers convened, he managed to escape, return to France, and briefly challenge his adversaries, before being defeated for the last time and sent to Saint Helena Island. With Napoleon out of the way, Europe’s monarchs, foreign ministers and diplomats proceeded to conceive a new world order — one in which great power politics prevailed. The Vienna settlement inaugurated the Concert of Europe, a period of peace and mutual understanding, based on friendly relations between the five most powerful countries of the continent: Austria, Prussia, Russia, France and the United Kingdom. It would take some revolutions and wars to overcome this arrangement.

Leave a Reply